When we run into a problem in everyday life- like planning a trip, fixing a Lego model, or managing a team- most of us instinctively try to move fast. We want to power through and fix things as quickly as possible. But what if going fast is not always the smartest move? What if slowing down, meeting a little resistance, or even stumbling a bit, is actually a necessary part of getting it right?

That is the big idea behind a talk by Bob Sutton, an organizational psychologist and author of The Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things Harder. He argues that not all friction is bad. In fact, some kinds of friction are essential.

Not All Friction Is Bad

Imagine a race car. The teams that win races are not the ones who press the gas pedal all the way, all the time. They slow down when going into corners. They pull into the pit for maintenance. If the car catches fire, they stop the race and get out. That kind of deliberate slowing down is not a sign of weakness. It is a necessary part of keeping things working – and sometimes, of staying alive.

In organizations, we often hear complaints about bureaucracy, slow approval processes, or frustrating rules. But Sutton wants us to ask a more important question. Is the friction we are experiencing stopping us from doing the right thing, or is it protecting us from doing the wrong thing?

A Life-Saving Rule in the Military

He gives a striking example involving Elizabeth Holmes, the former CEO of Theranos. Holmes pushed hard to get her company’s faulty blood testing device into military helicopters. She did not just pitch the idea – she enlisted a four-star general to pressure lower-ranking officials to approve it.

But those lower-level officers held their ground. They pointed to a rule: the device had to be approved by the FDA before it could be used in military operations. That rule acted as a kind of speed bump, an example of constructive friction. It prevented unproven and potentially dangerous technology from being used in high-stakes environments. In hindsight, that resistance was not a barrier. It was a safeguard.

Redesigning the Tampon the Right Way

In contrast, Sutton shares an encouraging story about a startup called Sequel, based in San Francisco. Sequel set out to redesign the tampon – a product that has gone largely unchanged for decades. But instead of rushing their product to market, they took the long road. They went through multiple rounds of development, repeated testing, and the full FDA approval process.

It was not easy. It was slow and filled with challenges. But now their product is out in the world, fully tested and legally approved. Sutton even mentioned that he invested twenty-five thousand dollars of his own money in the company – acknowledging that he might not get it back, but he believes in what they are doing. For him, Sequel’s story is a reminder that the hard path, with all its friction, can lead to meaningful, lasting results.

The Unsung Heroes of Friction Fixing

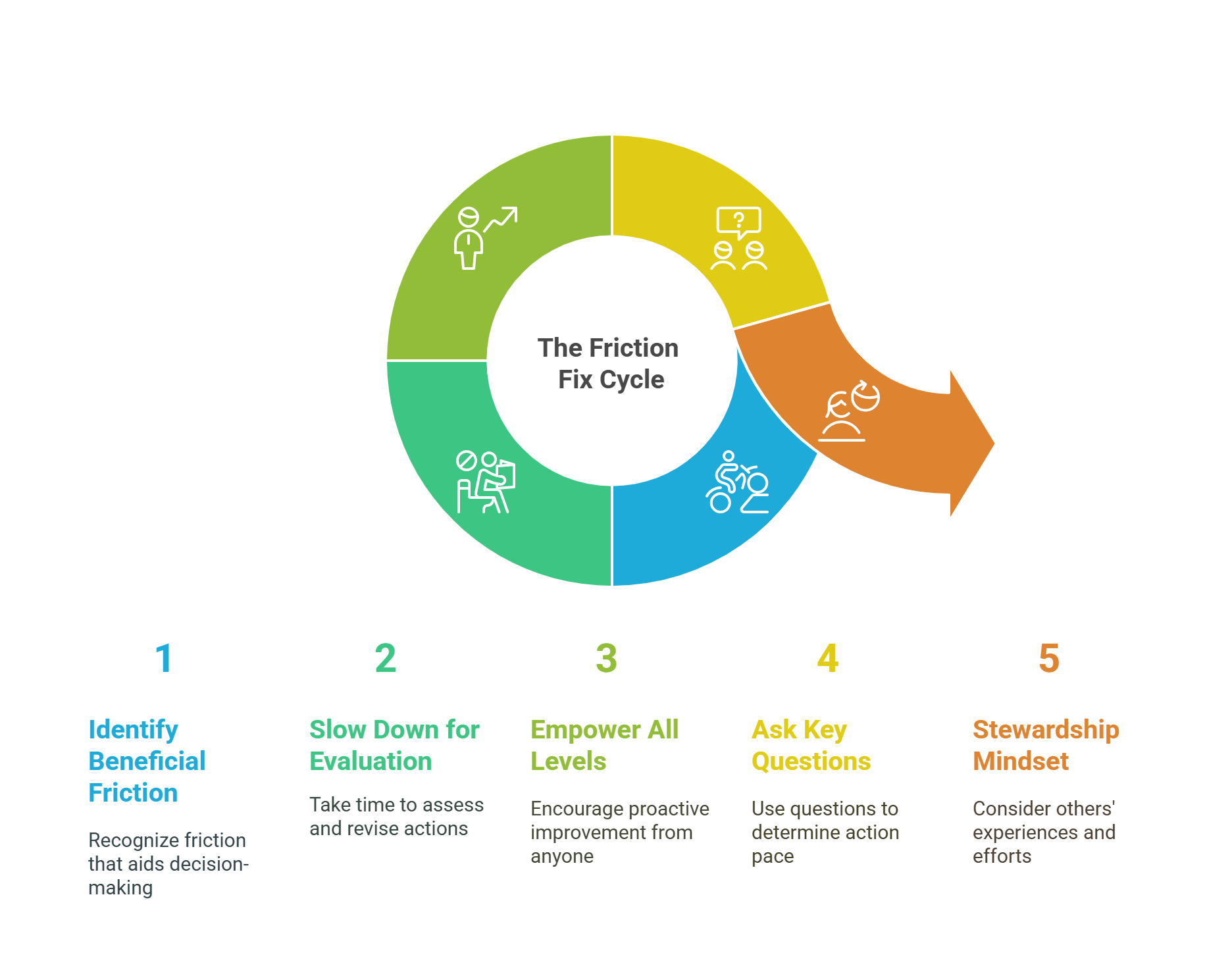

So what does it take to be a friction fixer – someone who knows how to navigate or even create friction for the right reasons?

According to Sutton, it is someone who constantly thinks about how their decisions impact others’ time and energy. It is someone who sees themselves as a steward, not just of outcomes, but of people’s experience along the way.

He shares an unexpected example from his visit to the Department of Motor Vehicles -a place many of us associate with endless waiting and red tape. Sutton arrived at 7:30 in the morning, expecting to lose most of his day in line. There were already about sixty people ahead of him.

But just fifteen minutes later, a man came out to the waiting area and began walking down the line, asking people what they needed. He clarified which services the DMV actually offered – sending away those who were there for things like passports, which could not be processed there – and gave forms and instructions to those who needed other services. Sutton was in and out of the DMV by 8:20. It was one of the smoothest public service experiences he had ever had, all because one person took the initiative to reduce unnecessary friction by respectfully guiding people through the process.

You Don’t Need a Title to Be a Friction Fixer

Sutton emphasizes that leadership is not required for this kind of impact. You do not have to be at the top of an organization to act as a friction fixer. In fact, some of the most effective changes come from people working on the front lines who understand where processes break down and can help make things smoother.

In his research, Sutton highlights two simple but powerful questions that great friction fixers ask.

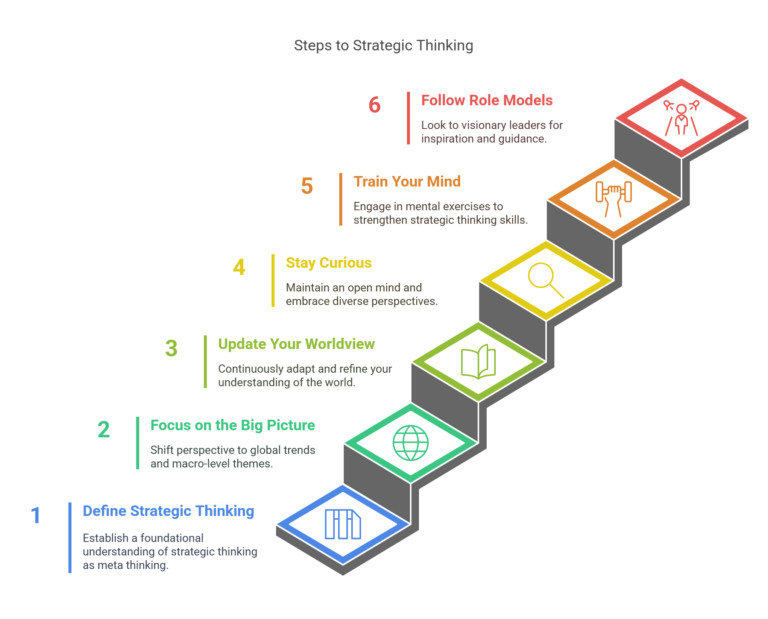

Question One: Do I Know What I’m Doing?

That question is about being honest with yourself. If you are in a familiar situation and everything is running normally, quick decisions can work. But if you are in a complex or uncertain situation – what Sutton calls a cognitive minefield – then it is best to slow down, step back, and sometimes do nothing at all until you understand the landscape.

One example of what happens when this question is ignored comes from the story of Google Glass. Sergey Brin, co-founder of Google, saw the product and fell in love with the idea. He got so excited that he pushed it into mass production, despite concerns from the development team that it was not ready.

The result was a major flop. The product had serious battery life issues, security problems, and an interface that left users confused. It ended up being labeled one of the worst product launches of all time. If Brin had paused, asked whether he truly understood what he was doing, and taken time to listen, Google might have saved themselves an expensive and embarrassing failure.

Question Two: Is This Decision Reversible?

If it is, you can experiment, prototype, and try things out. If it is not – if you are firing someone, selling your company, or making another high-stakes move – then you need to slow down and make sure you get it right.

Sutton tells a humorous and insightful story about David Kelley, founder of the design firm IDEO. When IDEO was still small, with only about fifty people, everything worked smoothly. But as they grew to 150 employees, the structure started to break down. Project staffing became confusing and disorganized. So Kelley decided to reorganize the company.

Just before the all-hands meeting, he shaved off his trademark Groucho Marx–style mustache. None of his colleagues had ever seen him without it – not even his wife, who screamed when she saw him. At the meeting, Kelley looked out at the team and said, “This reorganization is like my mustache. It is a reversible prototype. If it does not work, we can change it back – just like I can grow my mustache again.”

The point was simple but powerful. Some decisions are temporary and easy to revise. Others – like cutting off a finger instead of shaving a moustache – are permanent. Knowing which is which makes all the difference.

Slowing Down to Move Smart

Through these stories, Sutton offers a refreshing perspective on how organizations function. Friction does not always mean failure. It can be a signal. It can be a safeguard. And if you are thoughtful about when to reduce it – and when to build it in – you can make smarter decisions, protect your team’s time, and build processes that actually work.

Sometimes, going fast means knowing when to slow down.